"Young Hare" (after Albrecht Dürer), detail, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, inv. No.: 507379, current condition of the drawing

Source: Klassik Stiftung Weimar

The Klassik Stiftung Weimar keeps a coloured drawing on a calfskin parchment, which is generally regarded as a lesser-quality copy of the hare drawn by Albrecht Dürer, which is in the Albertina in Vienna. Although the drawing carries Albrecht Dürer’s monogram, it does not seem to be the master's own handiwork. Possible draughtsmen are considered to be Georg Hoefnagel (1542-1600) or Giuseppe Bossi (1777-1813). Previous restorative investigations have failed to date the drawing.

Prof. Oliver Hahn and Prof. Ira Rabin work at BAM’s Analysis of Artefacts and Cultural Assets Division and also at the Special Research Area 950 "Manuscript Cultures in Asia, Africa and Europe" of the University of Hamburg. In cooperation with their Weimar colleagues specialising in restoration, conservation and art technology, Mr Uwe Golle and Mr Carsten Wintermann, they once again looked at the issue of a possible author of the drawing. When and by whom was the hare drawn and how can this be determined without damaging the already fragile drawing?

Tracking the hare by X-ray fluorescence analysis

The Weimar drawing, which has already been investigated several times to determine the colourants used, is in a poor state of preservation. The surface is very dark, some parts are rubbed off and it shows signs of mould, and other parts have become blurred, presumably due to water damage. Therefore, it is hoped that imaging investigations will provide information about the origin of the drawing and form the basis for a reassessment of the artwork.

X-ray fluorescence analysis is a classic imaging technique used to investigate the elemental composition of materials – also in the analysis of artefacts and cultural assets. This method works as follows: a material sample is exposed to high-energy X-radiation. The radiation interacts with the matter and the excited atoms emit characteristic radiation of their own. This can be explained at the atomic level by the primary radiation interaction with the atom’s electron shell at the beginning of the X-ray fluorescence process. An electron close to the nucleus is then ejected from the atom’s electron shell and the atom is transformed into an energetically higher, excited state. However, the atom quickly returns from this excitation state to the ground state, because an electron from an outer shell will take the place of the ejected electron. The energy difference between the two states is emitted in the form of an X-ray quantum. This X-ray fluorescence detected by a suitable detector provides information as to which elements are present. The energy of the emitted X-ray radiation is characteristic of a certain chemical element and its signal intensity enables us to draw conclusions about the amount of the element present.

The curls provide information

The Weimar drawing of the hare was analysed using an X-ray fluorescence portal scanner at BAM’s Analysis of Artefacts and Cultural Assets Division in cooperation with the Collaborative Research Centre of the University of Hamburg. The XRF scan was carried out using a Bruker Nano Jet Stream equipped with a rhodium X-ray tube. The result is a number of element distribution maps that visually represent a distribution of certain chemical elements such as iron, lead and zinc.

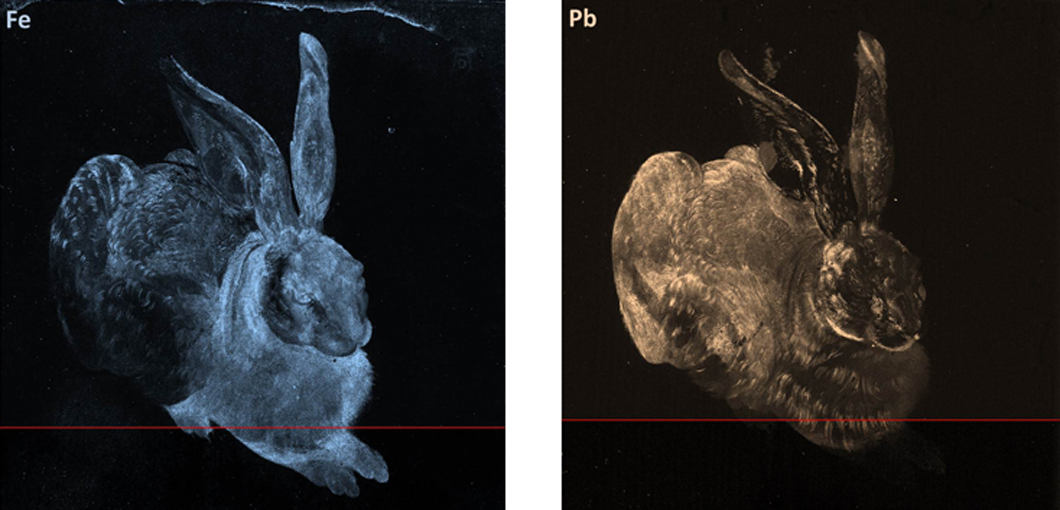

When comparing in a first step the present state of the drawing with the element distribution images of iron and lead, it becomes evident that the drawing of the fur is actually very fine. However, this graphic precision is no longer visible today due to the poor state of preservation.

Element distribution images of iron (Fe) and lead (Pb)

Source: BAM

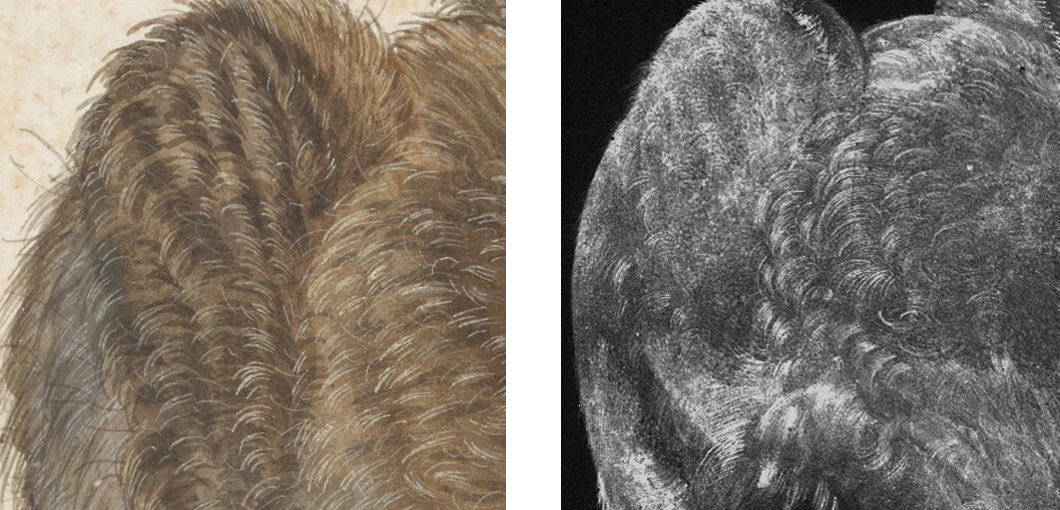

Upon a closer look at the element distribution pictures, it is concluded that the drawing cannot be a mere copy of "Dürer’s Young Hare". The painting style of the fur is completely different. "Dürer’s Young Hare" from the Albertina shows a straight-lined structure of the individual hairs, which is probably much closer to reality. In the Weimar hare, however, the hair is curled – which is another drawing technique. This suggests an earlier origin, thus neither Hoefnagel nor Bossi can be the author. However, this hypothesis would have to be verified by comparative art science analyses.

Detail of "Dürer‘s Young Hare" from the Albertina, inv. No.: 3073 (left); detail of the element distribution image of lead of the hare from the Weimar Graphic Collection (right)

Source: Albertina Collection online (left), BAM (right)

The distribution image of zinc conclusively explains the poor preservation state of the drawing. A substance has run over the middle of the drawing and damaged it. It was probably a paint that contained zinc white. The investigation also has shown that zinc-containing pigment was not applied over a large area of the drawing.

BAM is researching to further develop non-destructive analysis methods

The Weimar hare is a good example of how imaging techniques can change our way of seeing the artefact due to materiality visualisation. The finest lines and colour traces that cannot be detected by the naked eye become visible only when such methods are used.

The methods of material science have long been an integral part of investigations into artefacts and cultural assets. Non-destructive analyses enable investigations without sampling, thus protecting valuable objects. Imaging techniques such as computed tomography, radiography or multispectral analysis, are commonly used. They can visualise contents invisible to the human eye, such as preliminary drawings, pentimenti – e.g. colour or physical corrections undertaken by the artist – or internal structures. The resulting new images can change the way we see cultural artefacts because they provide deeper insights into the production process, structure or conservation status, and they document changes that have occurred in an object.

Thus, such analysis methods tell a lot about aspects of cultural history that cannot be answered by the methods of humanities research alone. In addition, they enable a characterisation of material damage caused by the environment. This is very important for creating suitable restoration or conservation strategies. In addition to the further development of non-destructive analysis methods, BAM also supervises these restoration and conservation measures.

Acknowledgement

This case study is based on the close cooperation between BAM, Klassik Stiftung Weimar and the Special Research Area 950 "Manuscript Cultures in Asia, Africa and Europe" funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).